No Time to Spare

On the poetry of Samuel Menashe

In the preface to his New and Selected Poems, the American poet Samuel Menashe (1925-2011) begins with a confession:

I never expected to meet a poet, let alone become one. Poets were dead immortals, some of whose poems I had by heart.

All of his life Menashe was a neglected master, with all of the strange glamour (and the poverty) that that entails, and he remained a neglected master even when, towards the end, there were people willing to describe him as such.

Now he is himself a dead immortal—and he is still neglected. His confession (as I call it) is characteristic for several reasons: first of all, in its humility; second, in its implicit recognition of his own isolation and his difference; and, third, in its language. For the phrase he uses—by heart—is surely a Menashe phrase: both very ordinary, and limitlessly beautiful. It is the kind of phrase we all use, all the time; and the kind of phrase whose beauty, unless we stop to look at it (or, in my case, unless we have to teach it to a foreigner), we may never notice.

In English, as Robert Graves observes, we can learn poems by rote or we can learn them by heart. I tend—given that I am neither an academic nor a journalist—to assess poets based on exactly how much of them I have by heart, how much of their work goes into me without my even knowing it.

The poem quoted at the top of this piece is the second part of Menashe’s poem ‘Curriculum Vitae’; over the long years, I have recited it, by heart, hundreds of times, usually when climbing the stairs of lonely Italian apartment blocks.

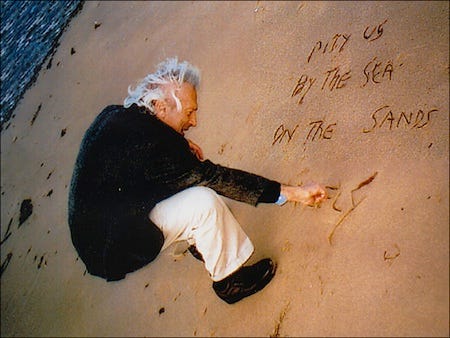

At fourteen lines, it is one of the longest poems in the New and Selected. When Menashe is known at all, he is known as a great miniaturist: one of the great miniaturists. Very few of the poems in the book are longer than a page; the majority (I’m guessing, from memory) are six or eight lines at the most; and some of them, like the untitled one that he is writing in the sands in the photo above, are mere words.

Pity us

By the sea

On the sands

So briefly

Sad Steps

It is not clear, therefore, exactly how to categorise these poems—if, indeed, we need to do so.

A few weeks ago on Substack, Jem wrote a brilliant piece about the middle distance poem: ‘a long-ish poem… written in regular, more or less metrical stanzas… a personal poem [in which] something, somewhere, is being worked out.’

I found myself, as I read that piece, trying to draw distance-analogies with other poems. If ‘The Whitsun Weddings’ is middle-distance, and Paradise Lost is a marathon (or maybe ten marathons), what then are epigrams or aphorisms or limericks? Jumps, perhaps, or jigs?

Menashe is none of the above: his poems, as Christopher Ricks says, are both ‘not epigrams exactly’ and ‘exactly not epigrams’. They lack the neatness and the resolution; though they might be comic in a broad religious sense (the sense in which the Divine Comedy is comic), they are not usually funny; they seldom have punchlines of any sort. The only distance-analogy I can think of is with a step: each of his poems is a few steps; sometimes, perhaps, a single step.

At the same time, they are not fragments. Unlike many of the great Imagist poems in English (to draw an analogy with some other miniaturists), Menashe’s poems always seem complete and whole.

Forever and a Day

No more than that

Dead cat shall I

Escape the corpse

I kept in shape

For the day off

Immortals take

Hermits

And so there may not be adequate comparisons for this in English: one comparison from outside of English, it occurs to me, might be the Italian exponents of so-called ermetismo (hermeticism). The best-known of them internationally (thanks to one of those yearly pronouncements from a committee of elderly Scandinavians) is probably Salvatore Quasimodo; in Italy, the best-known by far is Giuseppe Ungaretti, the author of what might be the most famous single poem in modern Italian literature.

Here it is:

Mattina

Santa Maria La Longa il 26 gennaio 1917M’illumino

d’immenso

With this, understandably, some of Ungaretti’s English translators don’t even bother: you get the original Italian, plus a footnote. Literally it says something like:

I illuminate myself

with immensity.

But, really, where would you begin? To translate it into English you would first have to translate it into Italian. And yet even many Italians who don’t read poetry know that poem, and remember it, just as I remember Menashe:

Beachhead

The tide ebbs

From a helmet

Wet sand embeds

The subtitle—and especially the date—of Ungaretti’s poem is important, just as the title of Menashe’s poem is important. The former was written in the trenches in the First World War; the latter, without doubt, arises from Menashe’s experience as an infantryman in the Second. Both poems, clearly, draw in a short space on massive recesses of trauma and wonder: ‘a whole war’—as Clive James, writing about Menashe, marvels in his Poetry Notebook—in a few words.

Syllables

Perhaps it would be better to say, in fact, that Menashe expresses ‘a whole war’ in a few syllables: for his poetry, as Ricks and Donald Davie both note, is poetry by the syllable. It does for the English language what the haiku does for the Japanese—or, perhaps more accurately, what the haiku normally does not do for the English.

Over and over again, the sheer smallness of the poems forces us to look at each syllable:

The Niche

The niche narrows

Hones one thin

Until his bones

Disclose him

In a certain narrow sense, this doesn’t really rhyme, at least insofar as it doesn’t have full end-rhymes; in another sense, like all of Menashe’s poetry (and perhaps like all poetry), every part of this rhymes with every other part: whether vocally (e.g. thin and him) or visually (e.g. hones and one).

One of Menashe’s favourite words (appropriately) is niche, which in his American accent sounds like the first syllable of kitchen:

At a Standstill

The statue, that cast

Of my solitude

Has found its niche

In this kitchen

Where I do not eat

Where the bathtub stands

Upon cat feet—

I did not advance

I cannot retreat

There are rhymes here hidden away in ordinary language, if only we know how to find them. And, if only we know how to find it, there is beauty as well: the beauty of etymology, whether it is made explicit, as in Adam Means Earth—

I am the man

Whose name is mud

But what’s in a name

To shame one who knows

Mud does not stain

Clay he’s made of

Dust Adam became—

The dust he was

Was he his name

—or whether it is merely implied, as in Improvidence (apparently a favourite of Milton Friedman):

Owe, do not own

What you can borrow

Live on each loan

Forget tomorrow

Why not be in debt

To one who can give

You whatever you need

It is good to abet

Another’s good deed

Again, the tiny size of the individual line—four assonant monosyllables, ‘owe, do not own’—forces us to look more carefully.

Analyses

High school students studying poetry, rather famously, get exasperated, rather easily, with the close-readings of the professors… and maybe we all do. When Ricks, for example, points out that Eliot’s line

Politic, cautious, and meticulous

happens to contain within it the attendant lord Polonius

Politic, cautious, and meticulous

we might (wrongly?) see only a bizarre coincidence. But when he does the same thing with Menashe, as in his introduction to the New and Selected, we cannot ignore it. In its entirety, Menashe’s poem ‘A pot poured out’ (the title on the contents page is more than half the length of the text) reads:

A pot poured out

Fulfills its spout

If there was a whole war in the lines that James quoted, there is a whole metaphysics here, and an intricacy that seems to increase the longer we spend repeating it: Ricks notes how the word pot is itself ‘poured out’ into the phrase poured out, and then again into the word spout…

Or look again at the end of the first one I quoted:

No name where I live

Alone in my lair

With one bone to pick

And no time to spare

Whether that penultimate line is intended to be a suggestive pun (which is how my hell-bound soul interpreted it), I don’t know; but I feel sure that Menashe must have intended the joke in the last line. This poem is long, by his standards, because he has had no time to make it shorter; no time to make it spare; no time to spare.

Commonplaces

‘No time to spare’, ‘Time and again’, ‘kept in shape’, ‘what’s in a name’—all of these are commonplace expressions; the sort of expressions writers are often encouraged not to use, or even to war against; the sort of expressions, notwithstanding, that all of us use almost all of the time.

Here the comparison with Ungaretti’s poem ends, for I illuminate myself does not sound much more natural in Italian than it does in English. Menashe’s language, read aloud as slowly as it should be, sounds both natural and unnatural: like Beckett, he never uses a commonplace expression in innocence, but always in order to play some sort of game with it.

In Beckett’s case, the games are often comic, as in this exchange from Endgame:

CLOV. Do you believe in the life to come?

HAMM. Mine was always that.

In Menashe (except in the broad sense mentioned above), it is not comic so much as worshipful; it is the supercharged language of the Hebrew prophets, or, at least, of the prophets as they come to us in English. The first poem in the New and Selected, the poem that threw Menashe into my life, is this:

Voyage

Water opens without end

At the bow of a ship

Rising to descend

Away from itDays become one

I am what I was

Here, again, is a whole war in six lines; here, again, is the suggestion of something absolute, something terrifying; and here again are the echoes (look at the last line) of Shakespeare and the King James Bible. The speaker is what he was—and what was that? Earth, like Adam? Or his background—the poet’s often-mourned mother and father? Or the past—the European theatre and its torpedoed ships? Or a being in time, just as another kind of being—the one who is that He is—is outside of time?

And here again, finally, is another ordinary expression:

Days become one.

The sinking ship is, obviously, a sinking ship, but at the same time it is life and it is death, the sinking ship on which we are all living. The ordinary idiomatic sense of this expression (that every day feels the same) seems here to take on a strange prophetic power, whether religious—that there will come a day whose sun will never set—or secular—that, on the day of your death, all of your days become this one day.

Days

By now, on the occasion of his centenary, Menashe’s one day has come, and he is left to posterity. Whether or not he is well-known among readers of poetry today is probably a question for someone else, i.e. someone who hasn’t spent the last fifteen years chain-smoking in a darkened room.

There are some videos of him on YouTube; some of his poems are on the Poetry Foundation website; and I have found a few mentions of him (including this fascinating recollection of the man and the poet) on Substack. But I think that he should be much better known than that.

I wanted to say thank you for introducing me. I started reading The Niche Narrows this week. It's a sort of spiritual vertigo, the reverberating way he arranges emblematic language. Beautiful, hard structure and sound too, poems of "ideal bone" [to flip his words]. Thank you.

An excellent and persuasive introduction (ditto for your Thomas and Smith essays) — I have admired stray poems of his in the past, but you demonstrate that he is worth exploring in earnest.

Interestingly, I have an entirely different reading of “Voyage.” I don’t believe the ship is sinking at all, it is simply cutting through the water as it moves forward. It is the water which is “rising to descend/away from it [the ship].” “Days become one” I read in the conventional sense, just as the uprisings of water flow together into a single foamy wake behind the ship. “I am who I was” is the speaker’s comparison of himself to the wake— he is merely the aftermath of prior events in his life, just as the existence of the wake is the record of the ship’s cutting through the water (time). The poem is called “voyage” because it is about identity-through-time, not mortality. But I don’t say any of this to quarrel, merely to offer a different perspective! I really admire the work you’re doing.