There I Go Again

On pessimism and the poetry of Stevie Smith

Without having intended to, I see that I’m writing essays about the poets who gave me comfort during my worst years. Previous poets include Samuel Menashe and R. S. Thomas: today’s poet is Stevie Smith.

Foolish illusion, what has Life to give?

Why should man more fear Death than fear to live?

(‘Come Death’ (i))1

Language pedants, as every reader of books in English knows all too well, are fond of complaining that the word unique is absolute—so that being very unique is like being very pregnant—just as they are fond of dismissing as clichés any number of user-friendly and fit-for-purpose phrases like user-friendly, fit-for-purpose, and beg to differ.

As usual, however, reality begs to differ. After eight months, a woman is very pregnant in a way that she was not after two months; just as there are cases when, comparing the work of any two given poets, we might easily find ourselves saying that the more original of the two is more unique.

This, at any rate, is my excuse for describing the poetry of Stevie Smith as extremely unique: the word unique alone, somehow, does not suffice…

‘The girl who disenchants’

At this point, Smith is generally accepted as one of the great poets of twentieth-century England. Generally—but not universally. There are probably more than a few reasons that any reader or critic might take against her (as some prominent ones have), and most of these reasons have something to do with her extreme uniqueness, her strange poetic voice.2

Smith portrayed herself, throughout almost all of her writing, as a kind of primitive, in the manner of Henri Rousseau or Jean-Michel Basquiat. Where they actually lacked artistic education, though, she only pretended to. Saturated as much as any great poet with the voices of others, she remained at the same time always and absolutely herself.

In a sense, she is as confessional as Plath—and yet seems to lack the supposed ‘authenticity’. She is as erudite and omnilingual as Eliot—and yet seems to lack the gravity. She is as readily comprehensible (and as pessimistic) as Larkin, and yet her work is often filled with madness, whimsy, and chaos.

Her poetic persona probably hasn’t helped. Though it is one of the reasons that she continues to be popular, it may also be one reason she is so often looked down upon: that persona might have been designed to irritate pompous Literary Men.

The persona was this: a middle-aged spinster, working an office job, living with aunts and with cats, speaking with the voice of a sad, self-pitying little girl, constantly suffering, constantly depressed, constantly dreaming of Death and of suicide. Some of the poems are archaic and Literary; others—apparently—far too simple. Many of them are filled with puns and silly jokes, or even accompanied by self-drawn cartoons of little girls or cats.

Smith was, in short, a misfit, and a misfit who wrote poems about, and for, misfits: sad people, ugly people, lost people, cat people; the Eleanor Rigbys of this world. She belonged to no movement and no school; she was never any kind of -ist. Like Larkin, she often appealed to people who did not normally read poetry: more than a few of her poems almost sound like the kind you might find quoted on fridge-magnets.3

As is not usually the case with fridge-magnets, though, she offered no easy answers. She didn’t seem to offer answers at all. Instead, her poems, as Larkin himself famously wrote, have ‘the authority of sadness’.4 She is a profoundly pessimistic writer, and her single most famous poem, which tells the story of a drowning man who from the shore appears to be waving, is one that the desperately optimistic might well characterise as depressing.

Nobody heard him, the dead man,

But still he lay moaning:

I was much further out than you thought

And not waving but drowning.Poor chap, he always loved larking

And now he’s dead

It must have been too cold for him his heart gave way,

They said.Oh, no no no, it was too cold always

(Still the dead one lay moaning)

I was much too far out all my life

And not waving but drowning.

‘Deeply morbid’

Stevie Smith’s ‘real’ life was, in many respects, exactly what you would expect from having read her poetry: emotionally tumultuous, artistically rich, and fairly uneventful.5

She was born in Hull in 1902, moved at the age of three with her family to London, and at some point in youth abandoned her given name, Florence, in favour of her androgynous pen-name. Her father, an English shipping agent, was mostly absent from her life: she grew up instead around women—her mother, her sister, her aunt—in what she called ‘a house of female habitation’ in North London.

She lived there—in that same house—almost all of her life, creating her own suburban territory in Palmers Green as surely as another extremely unique English writer, J. G. Ballard, created his in Shepperton.

Deeply morbid deeply morbid was the girl who typed the letters

Always out of office hours running with her social betters…

(‘Deeply Morbid’)

In 1936, she published Novel on Yellow Paper, her first masterpiece: a novel, presented as the chaotic musings of a bored secretary, which introduced that famous persona to the reading public. She worked for thirty years as a secretary to a publishing company executive; never married or had children; lived with her aunt and her cats; read and wrote and smoked a lot; and died of a brain tumour, at the age of 68, in 1971.

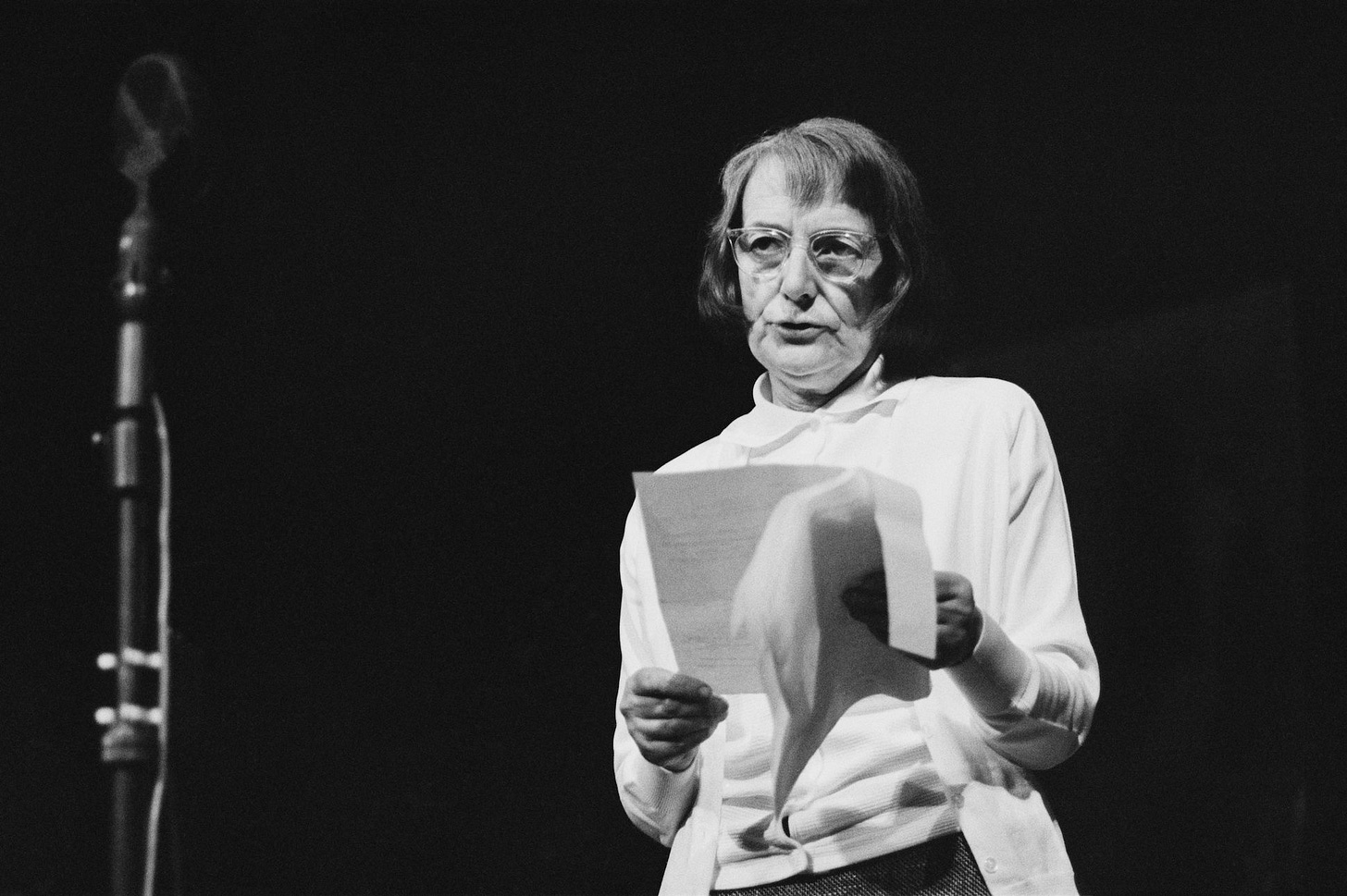

Happily, she found a popular audience while she was still alive, and became particularly well-known as a reciter (or performer) of her own poems on stage and on the radio. Her reading voice—now genteel and now ironic, with the cadences of plaintive sarcasm typical to her background—became famous in and of itself: the writer-director Jonathan Miller (whose family knew Smith when he was a child) described that voice as a cross between Mary Poppins and Laurence Olivier’s Richard III.6

‘Scorpion so wishes to be gone’

Miller’s remark is apt, and seems more apt—to me anyway—the longer that I look at it. What he said about Smith’s voice you could say also about her poetic voice: it sums up something of the strange mixture of the literate, cynical adult woman and the naïve, lost little girl.

Far and away the most noticeable quality of Smith’s poetry is that voice, the singsong girlishness, at the same time measured and conversational, apparently spontaneous and yet deeply considered:

I should like my soul to be required of me, so as

To waft over grass till it comes to the blue sea

I am very fond of grass, I always have been, but there must

Be no cow, person or house to be seen.

These lines are from the title poem of her last collection Scorpion. They seem straightforward enough, and characteristic; they mediate between apparently Poetic language (see the second line) and the excitable rhythms of speech (see the third); they look to God, and yet at the same time seem to make a god of Death—for having your soul required of you surely means Death.

It is simple and it is not simple. Very often, in Smith, there is something in the context complicating things: why, for example, is this poem apparently being spoken by a scorpion? And the context of her work in general is filled with complications: with puns, jokes, cartoons, music, foreign languages, scraps of poetry and theology, gallows humour…

The following example, for instance, with its overwrought language, is entertaining in and of itself:

Wretched woman that thou art

How thou piercest to my heart

With thy misery and graft

And thy lack of household craft.

(‘Wretched Woman’)

Yet it becomes more interesting (and more sinister) in context: when you see, accompanying it, the picture that she drew of a little child, who is speaking these exaggerated, melodramatic words, tugging at the apron of her weeping mother.

Equally, the following lines are entertaining, and seem lighthearted—that is, until you realise that they are being spoken by a cat.

Mrs Mouse

Come out of your house

It is a fine sunny day

And I am waiting to play.

(‘Cat Asks Mouse Out’)7

Both illustrate the kind of techniques that Smith played with constantly. This gallows humour, childishly expressed: naïve rhymes (‘Mouse’ and ‘house’); naïve pseudo-archaisms (‘that thou art’); naïve traditional metre (‘How thou piercest to my heart’); naïve anticlimaxes (‘And I am waiting to play’)…

‘He comes like a benison’

But, again, Smith is only pretending to be naïve. She knows, for example, how to write in set metres and forms, from the rhythms of the English hymnal to iambic pentameter:

Embosomed in the lake together lie

Great unaffected vampires and the moon.

(‘Great Unaffected Vampires’)8

At the same time—and probably for this reason—she is a thoroughly experimental writer. Experiment, in the arts quite as much as in the sciences, depends upon expectation: traditional forms carry expectations, and create them. There are limitless opportunities for experiment which arise from playing with those expectations: strange effects can be achieved when you do so.

That anticlimax in ‘Cat Asks Mouse Out’ for example, is achieved by the last line not having enough syllables. The anticlimax in ‘O Happy Dogs of England’, on the other hand, is achieved by having too many:

O happy dogs of England

Bark well at errand boys

If you lived anywhere else

You would not be allowed to make such an infernal noise.

For Smith, this life (as all of the quotations above make clear) is unsatisfactory, and anticlimax is a kind of denied satisfaction, the same denied satisfaction that you can see, in many cases, in the rhymes. She can withhold satisfaction, for example, by using half-rhymes—

Why do they grumble so much?

He comes like a benison

They should be glad he has not forgotten them

They might have had to go on

('Thoughts about the Person from Porlock’)

—but also by overloading the satisfaction with a double or triple rhyme:

By lions’ jaws great benefits and blessings were begotten

And so our debt to Lionhood must never be forgotten.

(‘Sunt Leones’)

‘Oh no no no’

Again, in all this we see both the cynical woman and the little girl: the relationship between the two of them turns out not to be unlike the relationship between the traditional prosody and the variations upon it. A persona might (etymologically) be a mask, but that does not make it untrue: the masks that poets wear, if they are good at what they do, become their faces.

Smith’s own persona bursts through even at those moments when she is communicating most closely with the past:

Paid weekly in an envelope

And yet he never has abandoned hope.

(‘Alfred the Great’)

The lion sits within his cage,

Weeping tears of ruby rage…

(‘The Zoo’)

No, I know nothing of Maud

I never wish to hear her name again

(‘Emily writes such a good letter’)

We are meant (I presume) to hear Dante, Blake, and Tennyson in these lines, but we also, unavoidably, hear Stevie Smith.9 In the same way her sheer emotiveness—all the pain at all the terrible suffering of her life and of the world—sometimes seems to burst through the stanzas, as it does in ‘Not Waving But Drowning’ (‘Oh no no no’), or as it does in another of her masterpieces, ‘The Frog Prince’:

Says, It will be heavenly

To be set free,

Cries, Heavenly the girl who disenchants

And the royal times, heavenly,

And I think it will be.

‘They laugh like anything’

Evident in most of the lines I have quoted so far is Stevie Smith’s other most noticeable quality: she is, broadly, a comic poet. This (of course) is another reason that she is sometimes looked down upon; it is also another aspect of her strange communication with tradition.

Humour, too, is a tradition to be played with, especially in the midst of suffering. Humour in the face of suffering seems inappropriate to some; to others, and perhaps especially to the English, there is no other kind of humour: all humour is gallows humour.

Until he remembered she came from the British Isles,

Oh, he said, I’ve heard that’s a place where nobody smiles.

But they do, said the lady, who loved her country, they laugh like anything

There is no one on earth who laughs so much about everything.

(‘The Hostage’)

More than a few serious poets, including many not from England, have played with the same effects as Smith: the forms of light verse coupled with distinctly unlight subjects. You can find such effects in the supposedly unserious poetry of the American Ogden Nash—

People expect old men to die,

They do not really mourn old men.

Old men are different. People look

At them with eyes that wonder when…

People watch with unshocked eyes;

But the old men know when an old man dies.

—but also in the serious poetry of the Australian Les Murray, as in this very disturbing example:

Age, spirit, kindness, all were taunts;

grace was enslaved to meat.

You never were mugged till you were mugged

on Aphrodite Street.

The effect of this tends to be creepy, unsettling, and not a little cruel: three epithets that could certainly describe the traditional humour of middle-class England. It is one of the things that, even today, disturbs people about British children’s literature, from the Alice books and Edward Lear all the way up to Roald Dahl.

Smith very frequently uses the style of children’s poetry to say rather adult things—which is to say, things that children might well understand, but which their parents probably hope that they don’t.

She said as she tumbled the baby in:

There, little baby, go sink or swim,

I brought you into the world, what more should I do?

Do you expect me always to be responsible to you?

(‘She Said’)

The speaker of this poem is only ‘she’, and could be any ‘she’. I hear a young woman, even an adolescent, which would certainly fit with this particular tradition. Smith, like Edward Lear and the rest of them, takes it as read that the cruelty of the world involves not only cruelty to children, but also the cruelty of children: as she writes of the Bacchae in Novel on Yellow Paper:

perhaps it is not very suitable for children, if you have that point of view about children.

‘A beautiful cruel lie’

In this sort of children’s literature, the figure of terror is often the father. In Lear, it is often just ‘they’, whoever exactly ‘they’ may be.10 Both of these can be found in Smith’s verse, from ‘Not Waving But Drowning’ (‘his heart gave way / They said’) to these lines from ‘Infant’:

Why is its mother sad

Weeping without a friend

Where is its father—say?

He tarries in Ostend.

(‘Infant’)

Either of these mysterious entities could be identified with God, who, for the most part in Smith’s poetry, is presented inconsistently (like these figures in children’s literature) as some combination of kindly, ridiculous, and unimaginably violent.

It is because I can’t make up my mind

If God is good, impotent, or unkind.

(‘The Reason’)

Smith was, more or less, an atheist: the God of her poetry is absent at best and vindictively cruel at worst. Even more than misotheistic, she was thoroughly suspicious of the clergy, seeing the Christianity in which she was raised as, for the most part:

a beautiful cruel lie, a beautiful fairy story.

a beautiful idea, made up in a loving moment.

(‘How Do You See?’)

Again, there is a tradition here: English political culture is shot through with anticlericalism, just as English poetry is shot through with godless pessimism, from Macbeth’s most famous soliloquy to ‘Dover Beach’ to Thomas Hardy.

Whether godless or not, Smith is certainly pessimistic. In that, the adult woman and the little girl are as one: they and other people are suffering; that suffering, they believe, should be taken seriously; and God, if He exists, evidently does not take it seriously:

What care I if good God be

If he be not good to me,

If he will not hear my cry

Nor heed my melancholy midnight sigh?

(‘Egocentric’)

This sort of question seems obviously pertinent to some people and obviously egocentric (see that title) to others, and the two groups are infamously bad at understanding each other. The pessimists see the optimists as offering not much more than a callous disregard for other people’s suffering; the optimists hear what the pessimists say and assume that they (we) cannot really mean it.

Stevie Smith, at least in my opinion, meant it. Though her attitude to Death (see below) is generally different from Larkin’s, her attitude to religion is mostly the same: the attitude which, contrary to some on the wilder shores of atheism, would say both that there is no god and that that is a bad thing. Indeed, in this view life itself is a bad thing, for the most part; nothing can justify all of this pain; the world is a site of ugliness and suffering occasionally interrupted by joy—and not the other way around.

Happiness is silent, or speaks equivocally for friends,

Grief is explicit and her song never ends…

(‘Happiness’)

‘Deceitful friend’

The challenge to anyone who sees the world in this way is clear enough: if life is as bad as you say it is, why is death not good? The answer, for Smith, is that it might well be: the view in her poetry, for the most part, is not Larkin’s terror nor Macbeth’s rage but something more like the view of Seneca, or indeed of another Shakespearean character, Claudio in Measure for Measure.11

Repeatedly, in Smith’s poetry, the figure of Death (almost always capitalised) comes as a friend, a saviour, even as the greatest of God’s blessings. Larkin himself quotes these mysterious, beautiful lines:

Why do I think of Death

As a friend?

It is because he is a scatterer,

He scatters the human frame

The nerviness and the great pain,

Throws it on the fresh fresh air

And now it is nowhere…12

But there are many other instances:

Smile pleasant Death, smile Death in darkness blessed

(‘The River Deben’)O Death, Death, Death, deceitful friend…

(‘When I awake’)My heart goes out to my Creator in love

Who gave me Death, as end and remedy.

(‘My Heart Goes Out’)

In one of her greatest poems, ‘Thoughts about the Person from Porlock’, which has comforted me since I first read it as a teenager, Smith identifies Death with the title character: i.e., with the man who supposedly interrupted Coleridge during the writing of ‘Kubla Khan’.

According to Coleridge, this man, who broke the flow of poetic inspiration, was the reason that ‘Kubla Khan’ comes to us as a fragment. Smith’s poem, which is also a series of fragments, sees things rather differently: Coleridge, after all, did not have to let the man in; he let him in because he wanted to; and the speaker, given half the chance, would do the same; she would welcome the interruption; she would welcome Death.

I long for the Person from Porlock

To bring my thoughts to an end,

I am becoming impatient to see him

I think of him as a friendOften I look out of the window

Often I run to the gate

I think, He will come this evening,

I think it is rather late.I am hungry to be interrupted

For ever and ever amen

O Person from Porlock come quickly

And bring my thoughts to an end.

‘Ah me, sweet Death’

Some people will not understand ‘Thoughts about the Person from Porlock’, just as they will not understand the Stoic pessimism that Smith expresses in these lines (the italics are mine) in ‘What Poems are Made of’:

It is pleasant, too, to remember that Death lies in our hands; he must come if we call him. ‘Dost thou see the precipice?’ Seneca said to the poor oppressed slave (meaning he could always go and jump off it). I think if there were no death, life would be more than flesh and blood could bear.

To such people, the fact that I drew (and draw) comfort from such lines will seem inexplicable: they might look on Smith’s sentiments as impossibly unhelpful, or even dangerous. Judging by her popularity, though, there are many others like me, who find both wisdom and beauty here, in the realisation that they are not crazy for thinking as they do, that life can be very funny even when it is horrible, and that, one way or another, there will certainly be an end to our suffering.

Ah me, sweet Death, you are the only god

Who comes as a servant when he is called…

(‘Come Death’ (i))

Well-meaning friends and family, horrified at hearing such morbid language from people they love, tend to react with panic: as if they are witnessing an attempted suicide take place. And yet there is all the difference in the world between talking about suicide and attempting it; if someone is in the process of talking to you, however terrifyingly, then they are not, in that moment, attempting it; there can be a cathartic benefit, for people filled with black bile, to simply let it out by talking.

When that talking is done by someone else, in poems as achieved and as funny as Stevie Smith’s, it is more than cathartic: it provides the kind of connection with other human beings that makes life worth living—if, indeed, it is. Here, on the page, is someone who understands; who takes your suffering seriously; you are not alone. For all their pain, that person also sees better things in the world—if nothing else, then in the very act of writing a poem. Great art is affirmative in and of itself, just by existing; it gives consolation even when it confronts the horrible truths of this world.

For some people, like Stevie Smith, and like the poor man in ‘Not Waving But Drowning’, almost all of the truths about this world are horrible. For a lot of people, a lot of the time, this life is a nightmare, but there is literature even for us. Perhaps especially for us.

Stevie Smith belongs in the pantheon of such literature. She is flippant, funny, intense, serious, morbid, clear-eyed, compassionate, and ruthless. And there will always be some, like me, who need that utterly individual, extremely unique voice:

These thoughts are depressing I know. They are depressing,

I wish I was more cheerful, it is more pleasant,

Also it is a duty, we should smile as well as submitting

To the purpose of One Above who is experimenting

With various mixtures of human character which goes best,

All is interesting for him it is exciting, but not for us.

There I go again. Smile, smile, and get some work to do

Then you will be practically unconscious without positively having to go.

The poems by Stevie Smith quoted here come mostly from Selected Poems (edited by James MacGibbon) and Stevie Smith: A Selection (edited by Hermione Lee).

Dame Helen Gardner, for example, apparently dismissed Smith as a writer of ‘little girl poetry’.

This rhyme, for example, which is accompanied by a strange cartoon of an androgynous figure alone in a room:

Aloft,

In the loft,

Sits Croft;

He is soft.

See ‘Frivolous and Vulnerable’ in Larkin’s Required Writing.

This biographical information comes from the two anthologies, this article by Hermione Lee in the NYRB, and Poetry Foundation here and here.

Quoted by Lee.

This example, again, comes from Hermione Lee, who also points to trochaic tetrameter in ‘The Airy Christ’ and ballad metres in ‘To the Tune of the Coventry Carol’.

These examples are my own, but there are many others. Lee hears Housman, for example, in ‘Night-Time in the Cemetery’; Clive James hears Twelfth Night in ‘Come, Death’.

From George Orwell’s essay ‘Nonsense Poetry’:

Aldous Huxley, in praising Lear’s fantasies as a sort of assertion of freedom, has pointed out that the ‘They’ of the limericks represent common sense, legality and the duller virtues generally. ‘They’ are the realists, the practical men, the sober citizens in bowler hats who are always anxious to stop you doing anything worth doing.

Act three, scene one:

If I must die,

I will encounter darkness as a bride,

And hug it in mine arms.

This essay is my jam. I'm so fortunate to have found your Substack. And yes, talking about it all the time, and reading my favorite writers, keeps me from the beckoning balcony. I keep it close so it won't surprise me.

What an excellent essay! Subscribed.