Memento Mori

On Philip Larkin's 'Aubade' - and its discontents

I’m thinking of a new series of essays on great poems sometimes deemed to be ‘problematic’. This essay is about Philip Larkin’s ‘Aubade’, which can be read here and listened to here. Some of my other poetry pieces include essays about Samuel Menashe, R. S. Thomas, and Stevie Smith.

Part One

‘That green evening…’

‘Why do I think of Death / As a friend?’ asks Stevie Smith, and that—as people say when they are unsure how to respond to something disconcerting—is certainly a point of view. It may even be a necessary point of view: at least, for those of us denied the more obvious comforts of immortality.

It is one way of coping with the Reaper: historically, it finds perhaps its most familiar expression in the philosophy of Seneca, for whom dying well means dying gladly. Though Death, in this view, may well increase the sufferings of the world, it will only do so insofar as it is something that happens to the living: it will not be a source of suffering to the dead, since it will not, as such, happen to them. Rather, the day of my death will be release from and end to my sufferings. Furthermore, insofar as those sufferings are caused by Death—the pain and the fear I feel at the deaths of others, the dread I feel at the thought of my own—my death will also be, in some sense, a release from Death itself.

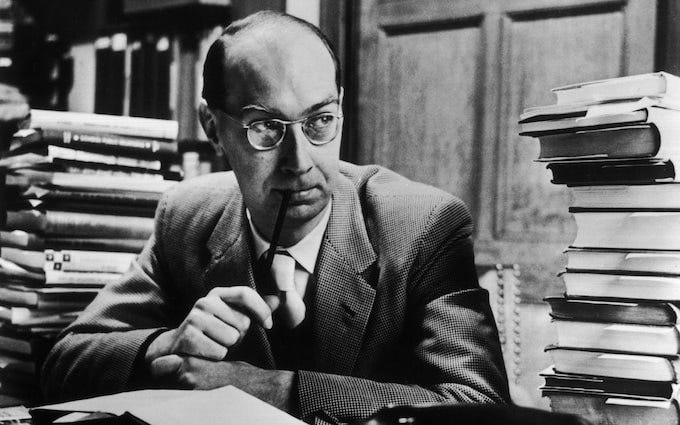

Perhaps surprisingly, given his reputation, something of this attitude can be found at times even in the death-obsessed poetry of Philip Larkin, for whom life, as it was for Seneca, is ‘slow dying’.1

I see traces of the attitude, for example, in the second of the mantras that he repeats in his poem ‘Wants’:

Beneath it all, desire of oblivion runs.

I see it in ‘the evening coming in’ that he sees in ‘Going’—

Silken it seems at a distance, yet…

And I see it, too, in the sudden beauty of his line in ‘Continuing to Live’—

On that green evening when our death begins…

‘Unresting death…’

Notwithstanding this, Philip Larkin is much more famous for thinking of Death in a rather different way, just as he is famous—like his weirdly parallel opposite number in America, Woody Allen—for thinking about it constantly.

It probably does not need to be said that, for the most part in Larkin’s poetry (just as in Allen’s films), Death is most certainly not a friend. On the contrary, Death is an enemy, the enemy; Death is bad. And the fact that Death is bad has consequences for Life, which is also bad. Life is bad, in part at any rate, because of Death, and Death is bad because Life is bad because of it: because of all the sufferings—the dread, the grief, the sadness, the futility, the physical pain—that Death causes to the people who are not yet dead.

Death is terrifying to Larkin (as to Allen) because it is nothing, and because nothing comes from it; even if, seen from another angle, everything seems to come from it, as if all the illusions we cling to—Reason, God, progress, posterity, moral order, heaven—are really Death’s children. Death is the great oppressor, the sapper of meaning, the black cloud constantly hanging in the sky, the persistent dripdripdrip of a tap in the next room, sending us off to sleep in the naked silence and waking us up before dawn.

This is what Death is in Larkin’s late poem ‘Aubade’, one of his best-known, most loved, and (occasionally) most hated poems. An aubade, traditionally, is a song at the break of dawn, and so, bleakly, is Larkin’s, before the break. It begins:

I work all day, and get half-drunk at night.

Waking at four to soundless dark, I stare.

In time the curtain-edges will grow light.

Till then I see what’s really always there:

Unresting death, a whole day nearer now,

Making all thought impossible but how

And where and when I shall myself die.

Arid interrogation: yet the dread

Of dying, and being dead,

Flashes afresh to hold and horrify.

There it is, then, from the very beginning, as stark as that. Unresting death: nothing in the remaining forty lines of the poem is less recognisable, or cheerier, than that.

In ‘Aubade’—as in Larkin’s mind more generally—Death is always ‘on the edge of vision’, omnipresent; there is ‘nothing more terrible, nothing more true’; the dreams of religion and philosophy (from the immortality of the soul to Seneca’s morbid friendship) are invented in order to deny it, simply or complicatedly:

This is a special way of being afraid

No trick dispels. Religion used to try,

That vast, moth-eaten musical brocade

Created to pretend we never die,

Or specious stuff that says No rational being

Can fear a thing it will not feel, not seeing

That this is what we fear…

In one of Allen’s later films, Deconstructing Harry, the Philip Roth-esque title character concludes that all people know the same truth, and our lives consist in how we choose to distort it. The same could certainly be said of (and by) the speaker in ‘Aubade’: although in this instance it seems truly impossible not to think of the speaker as the poet himself.

For Larkin then, Death is ‘unresting’; we know it, always, and feel its presence, almost always. In our everyday lives, we are at any given moment trying, if we possibly can, to distract ourselves from it:

And realisation of it rages out

In furnace-fear when we are caught without

People or drink.

It is on its way, now, like that evening coming in across the fields. And though, again, it is in this view thought of as an enemy, it doesn’t, at the same time, really matter how we think of it: whether it is friend or enemy for us, a ‘green evening’ or the sky as ‘white as clay’, the result is the same.

Courage is no good.

It means not scaring others. Being brave

Lets no one off the grave.

Death is no different whined at than withstood.

‘Groping back to bed…’

Most of Larkin’s readers regard ‘Aubade’ (correctly) as one of his masterpieces; perhaps, along with ‘The Mower’, the last great poem he published in his lifetime. Like his other masterpieces, it is a model of formal perfection, a made thing that does not seem made: that seems, rather, as though it had been discovered instead of written.

It is not so easy, in reality, to maintain a series of ten-line rhymed stanzas for two pages without drawing too much attention to your technique, but Larkin is able to do that, and the voice of this poem, as in so many of his others, never sounds less than natural: it sounds, indeed, almost prosaic, though at the same time it is precisely not prosaic.

What is true for the stanzas is as true for the language of the individual lines, and this is perhaps Larkin’s special genius: his ability to seamlessly combine, without ever fudging the metre, the idiomatic and the lyrical. In another masterpiece, ‘Sad Steps’, the opening begins with ‘Groping back to bed after a piss’ and ends with ‘the rapid clouds, the moon’s cleanliness’; in yet another, ‘High Windows’, he can go from ‘free bloody birds’ to ‘the sun-comprehending glass’ in the space of two lines. In the final stanza of ‘Aubade’, too, is the same balance, moving as it does imperceptibly from ordinary language—

what we know,

have always known, know that we can’t escape,

yet can’t accept.

—to the out of the ordinary:

Meanwhile telephones crouch, getting ready to ring

In locked-up offices, and all the uncaring

Intricate rented world begins to rouse.

‘Nothing to be said…’

The truth that ‘Aubade’ expresses—if it is a truth—has resonated, and resonates, with thousands of readers. We feel that way, too, at least some of the time; and here is someone who has given expression to those feelings, those thoughts, even as so many others deny or forbid or rage against them.

Larkin, seldom a very difficult poet in any case, has never been more straightforward than he is here: the sentiments, like Death itself, are immediately, starkly comprehensible to anyone who reads the poem.

Slowly light strengthens, and the room takes shape.

It stands plain as a wardrobe…

For all of these reasons, ‘Aubade’ bothers some people, those who either do not think this way, or who do think this way but would rather not. Those people might not know what to say to those who love the poem. And vice versa, of course: we who do love the poem may find it a difficult one to defend, since for us it requires no defence. What is there to say?

Only something, perhaps, like what Larkin himself says, at the end of another poem. This is one of the ways in which we live our lives, after all—

And saying so to some

Means nothing; others it leaves

Nothing to be said.

Part Two

‘It’s a hateful poem…’

Either in spite of its bleak sentiments or because of them, Larkin’s ‘Aubade’ is a companion to its many re-readers, a hand reaching out from the void to take theirs; it is also, in its formal beauty and its honesty, a kind of comfort.

Notwithstanding that, it may well be that to some others the poem means nothing: either insofar as they do not like it, or insofar as they think it is nihilistic—which, inasmuch as that word means anything at all, it clearly is.

As with most art deemed nihilistic—again, see Woody Allen’s films—or for that matter the poetry of Leopardi, the aphorisms of Cioran, the plays of Beckett, the novels of Céline—there is also a third group: those to whom the poem certainly means something but who do not, on the contrary, feel that there is nothing to be said.

One member of this latter group was the Polish poet Czesław Miłosz, to my knowledge the single most distinguished writer to have hated ‘Aubade’. Seamus Heaney, too, was troubled by the poem, and compared its despairing attitude unfavourably with what he found in Yeats, but in this regard Heaney is more temperate than Miłosz.2

He is also less obsessive: Miłosz seems to have returned continually to ‘Aubade’, attacking it from every angle that he could find for decades on end. Heaney, for instance, quotes the following sentiment, from a 1979 interview Miłosz gave to Poetry Australia (the italics are mine):

…the poem leaves me not only dissatisfied but indignant, and I wonder why myself. Perhaps we forget too easily the centuries-old mutual hostility between reason, science and science-inspired philosophy on the one hand and poetry on the other? Perhaps the author of the poem went over to the side of the adversary and his ratiocination strikes me as a betrayal?... poetry by its very essence has always been on the side of life.

This is already fairly intemperate, and, though it evidently resonates with Heaney, it speaks at the same time of a vague discomfort (‘dissatisfied’, ‘indignant’) and an uncomfortable vagueness (‘its very essence’, ‘the side of life’).

Years later, in his Paris Review interview in 1994, Miłosz was even more forceful:

I know Larkin’s ‘Aubade’, and for me it’s a hateful poem. I don’t like Larkin at all.

Some time later, perhaps with the dawning realisation that some people might think he was protesting much, he tried saying the same thing again, this time disguising the rage with glib condescension:

My dear Larkin, I understand

That death will not miss anyone.

But this is not a decent theme

For either an elegy or an ode.3

‘All do as I do…’

I first became aware of Miłosz’s dislike of the poem from the following remarks, which are quoted here and which come from the book Conversations with Czesław Miłosz. In these lines all of the angles—vagueness, indignation, and condescension—are combined in a single paragraph. Again, the italics are mine:

I guess it is correct to say that every poetry is directed against death—against the death of the individual, against the power of death. That’s why I was so angry a few years ago when I read a poem by Philip Larkin on death, a desperate poem about the lack of any reason—about the complete absurdity of human life—and of our moving, all of us, toward an absurd acceptance of death, which is true. But the poet shouldn’t do that. The poet shouldn’t take a passive attitude—how do I explain, it is very difficult—an attitude of complete submission to the absurdity of human existence.

The playwright Alan Bennett (who incidentally takes issue, as Heaney does, with Larkin’s remark above about ‘courage’) once observed that most of the pronouncements that writers make about their trade can be summarised with the words All do as I do.4 This is always useful advice to remember, in general, when reading or writing about poetry, and it is particularly useful whenever anyone invokes a supposed rule about what ‘the poet’—whoever he or she may be—should do.

Having read ‘Aubade’, Miłosz, evidently, would like to invoke such a rule, and makes vague attempts to do so—the poet shouldn’t take a passive attitude, the universality of death is not a decent theme—though, as usual in such cases, it is tempting to suppose that he has invented these rules only after discovering that Larkin has broken them.

Though Miłosz is too honest to pretend that his reaction is not an emotional one, he still tries to insist that it is intellectual as well. Nonetheless: all do as I do—that is a fair summary. Miłosz was (beyond doubt) a courageous man: he didn’t take a passive attitude, and nor, he thinks, should Larkin.

‘On the side of life…’

None of this is to say that Heaney or Miłosz have not found something interesting to say about ‘Aubade’, whatever the conclusions that they draw from it. Each of them both finds the despair of the poem troubling and finds it to be well-written, and each of them, in his way, is disconcerted by this. Understandably so: on the face of it, after all, that any poem should be as despairing as ‘Aubade’ seems almost paradoxical. How can such a poem exist in the first place, when it seems as if no one who feels this way could bring themselves to write a poem at all, and in fact would simply get full-drunk at night and leave it at that?

Heaney, sensibly, draws the conclusion that the poem, like any achieved poem, must somehow be ‘on the side of life’, if only by definition: a version of the same conclusion that Leopardi reached about any art which confronts the nothingness of things.5

Miłosz, on the other hand, cannot quite say that: rather, he is enraged by the dissonance that the poem creates for him. For him, being ‘on the side of life’ seems to mean more than it does for Heaney: seems, in fact, to imply a very definite point of view. (Immediately after saying that poetry should be ‘on the side of life’, he starts to talk about ‘faith in everlasting life’—which, needless to say, is not the same thing.) ‘Aubade’, for Miłosz, does not promote that point of view, and therefore is not on the side of life. Instead, it probes at something dark and hopeless in human hearts: in short, its view of Death (and therefore of Life) is, to use the vogue word, problematic.

‘Aubade’ probably is problematic, if any poem is—though, as ever with that designation, this should be the beginning of a conversation and not the end of one. For us now, in the twenties, problematic is all too often the end of a conversation: sometimes given as a reason not to read somebody. It shouldn’t be, however, and certainly isn’t for Larkin’s poem, which any lover of English poetry should read and confront. And we know, or should, that there is always more to be said: for in order to be meaningfully problematic, you have to be worth reading in the first place. (Nobody wastes time calling Mein Kampf problematic.) ‘Aubade’ is problematic for Miłosz because he can see that it is beautiful: if it wasn’t, after all, what would the problem be?

Whatever he is saying, or close to saying, in The Paris Review, Miłosz knows that Larkin is worth reading. In order to attack the poem, he therefore has to find some other angle rather than the aesthetic. And so: ‘the poet shouldn’t take a passive attitude’. With this remark, he is near, consciously or not, to echoing one of the stupider pronouncements of Yeats, who in his blanket dismissal of the war poets once famously remarked:

‘Passive suffering’ is not a theme for Poetry.6

Whether or not they have read that line in Yeats, Larkin’s readers will know it, since Larkin himself quoted it, if only in order to deride it, and countered it with a line from the greatest of those war poets, Wilfred Owen:

Above all, I am not concerned with Poetry.7

Indeed. Again, perhaps, there is nothing to be said.

To those who love it, ‘Aubade’ is beautiful in itself: in it, we see Larkin and we see ourselves. No aspect of life—though this may be an article of faith on my part—is an unfit subject for a poem, and passive suffering, needless to say, is an aspect of every life: no poet, however drunk or Welsh he may be, can spend all his time raging against the dying of the light.8

Those who are concerned with poetry (or even with Poetry) might therefore ask why passivity is not as fit for the likes of poets as for everybody else. Heaney rationalises his reaction as best he can; though Miłosz tries, somewhat feebly, to do so, his ideological commitment to Catholicism shines through, and the assertions he falls back on seem, for all his brilliance, to be threatened, insecure. After all, why can’t a poet take a passive attitude? Isn’t death a perfectly good subject for an elegy or ode? Aren’t there any number of good examples of that? And, furthermore, must we always be caged birds singing of freedom? Can we not sing about the cages as well?

No answer to these questions is forthcoming. Miłosz cannot quite account, intellectually, for his feelings—and it is worth asking why those feelings were of anger, of all things, upon reading ‘Aubade’. Not pity, not despair, not disgust: anger—the small anger of indignation (as in the first excerpt quoted) or the large anger of hatred (as in the second). Why?

We all know, if we read them, that poems do occasionally make us angry—any reader will be able to think of examples—and poems might do so for various different reasons. We might feel angry at a poem, for example, if it is badly-written (especially if it is also admired, while our own works of genius are not). Or we might feel angry because a poem is cruel: as Nabokov felt angry towards Cervantes, or as any sane reader will feel angry, at times, towards Ezra Pound. Or we might feel angry if a poem tells us easy lies, and especially the sort of lies that inadvertently remind us of the truth, as sentimental poems do, or as propaganda does.

Miłosz does not suggest that Larkin’s poem is badly-written: as, indeed, it is not. (Even alongside the strong sentiments in The Paris Review, he calls Larkin a ‘wonderful craftsman’—‘craftsman’ being the usual word used when a poet is good and you don’t want to admit it.) Nor does he suggest that Larkin is cruel, exactly: Larkin’s pain is so naked that he does not come across as cruel. Although we can imagine a hostile reader thinking that ‘Aubade’ might hasten someone’s hands towards the noose, Miłosz does not exactly convict Larkin, either, of being a Bad Influence. Does he think, then, that Larkin is lying, either about what the world is, or about what he himself feels towards it?

‘Denouncing suicide…’

The curiously hostile nature of Miłosz’s reaction puts me in mind of an observation by Schopenhauer who, in a famous essay, turns his attention to the act of suicide, which, in keeping with his general philosophy, he sees as a mistake but not as a crime.9

Many people, of course, have seen it as a crime, and those who do, he points out, are often vehement (not to mention cruel) in their condemnation of it, and of those who have carried it out. Christians, Jews, and Muslims alike line up to condemn it: many of them talk against suicide with the same fervour that they talk against homicide—and this phenomenon, furthermore, is not universal. (Again, for example, Seneca does not share it.)

So where does this vehemence come from? asks Schopenhauer. It is not after all (he says) based on scripture. Nor is it based on arguments—or, at least, not on good arguments. It is not even, if we think about the matter calmly, based on intuition: if a friend of yours killed herself, after all, would you really react in the same way as if you heard she had killed someone else? But then why all the abuse—the bigotry, the lack of compassion? The answer that Schopenhauer arrives at resounds across eternity: suicide, he says, is a poor compliment to the one who said all things were very good; the monotheists denounce suicide in order to avoid being denounced by it.

Is it fanciful to see something like this in the attitude of Miłosz—committed, as he was in some sense, to believing that all things are very good? Is it fanciful to see it in anyone who would denounce ‘Aubade’ in particular, and the poetries of ‘passive suffering’ in general? If your worldview tells you that it is not possible for a poem to be both nihilistic and great, then it is understandable that evidence to the contrary might disturb you, since by implication it disturbs your worldview as well. You say ‘the poet’ shouldn’t do something… but in the realm of poetry what is the difference, in the end, between saying a poet shouldn’t do something and saying that he can’t?

‘Aubade’ goes on being read, notwithstanding the efforts made to define it out of existence: Larkin can do this, clearly, because—look—he has done it. Yeats, Heaney, and Miłosz imagine for ‘the Poet’ certain responsibilities that, in the end, come from outside poetry, for quite other reasons than the aesthetic. For some people (or maybe I should say: for me) the only thing poets should do is write poems, and, though that is not synonymous with telling the truth, it entails telling the truth—or, at least, telling the truth as you see it, whatever the complications may be in figuring out what that means.

To those who love it, ‘Aubade’ is great for this reason: affirmative in and of itself (again, as Heaney recognised), but also consoling, insofar as it presents us with a beautiful image of a truth that we recognise and so often try to evade. It is hard to avoid the suspicion that that is the reason that Miłosz was made angry by it, in the same way that some of the monotheists are made angry by suicide: in other words, not because the poem lies, but because it does not.

All quotations from Larkin’s poetry here come from The Complete Poems (ed. Archie Burnett).

See Heaney’s essay ‘Joy or Night’, collected in Finders Keepers.

At least, the English translation appeared ‘some time later’ in ‘Against the Poetry of Philip Larkin,’ New and Collected Poems (trans. Miłosz and Robert Hass).

See Bennett’s Untold Stories.

See Leopardi’s Zibaldone (#259-260).

See Yeats’s preface to The Oxford Book of Modern Verse.

See Larkin’s Required Writing.

The example is not accidental. According to Patrick Kurp, Miłosz absurdly praises ‘Do Not Go Gentle Into that Good Night’ as expressing a ‘masculine’ attitude to death while deriding Larkin’s, for reasons best known to himself, as ‘effeminate’. Why being ‘effeminate’ might be a bad thing is unclear to me: nonetheless, it is not typically an adjective applied to Philip Larkin.

See ‘On Suicide’ in Parerga and Paralipomena Vol. 2 (trans. E. F. J. Payne).

Fantastic! So much to unpack here!!!

Thank you for this wonderful piece! Aubade has given me lots of joy over the years, even though I strongly disagree with it.